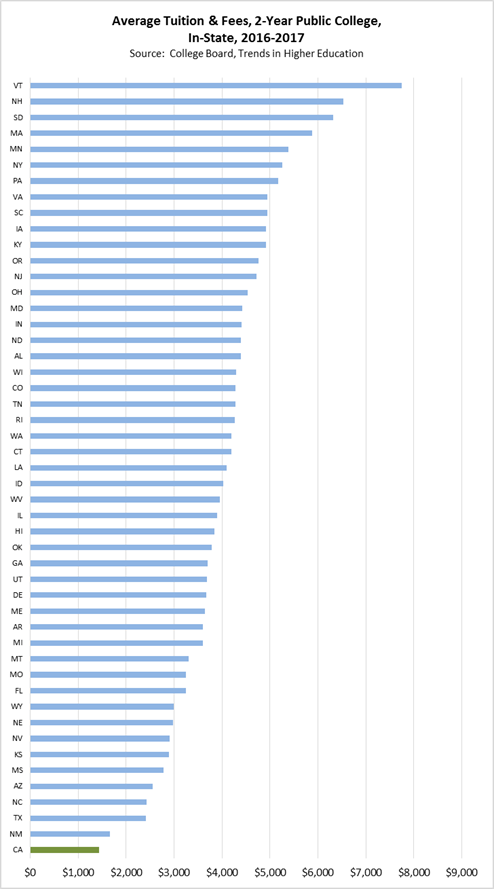

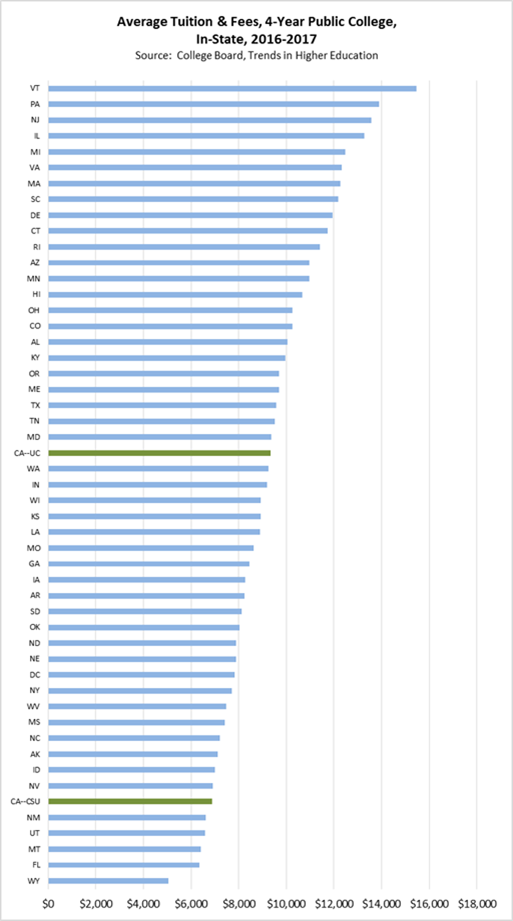

Average California tuition and fees for public higher education are already some of the lowest in the nation—the lowest of all the states for 2-year, Community Colleges.

Due to California’s High Housing Costs, Total Annual Costs Escalate Quickly Depending on Whether Students Live At Home or Off Campus

Recent analysis by LAO stated that after factoring in housing costs, total annual costs for attending Community College in California goes from the lowest to the 7th highest in the nation for students not living at home with their families. The following LAO conclusions were based on 2013-14 data. California housing prices have escalated rapidly since then.

In 2013-14, the average cost of attendance in California was $7,268 for students living off campus with family and $18,144 for students living off campus not with family. An estimated 57 percent of community college students live off campus with family and 42 percent live off campus not with family. The remaining 1 percent live on campus.

. . . The cost of attendance in California for students not living with family is higher than most other states. This is because California tends to have higher costs for housing, which is a large factor in attendance costs.

For students living with family, the cost of attendance in California is lower than all but six states. This is because housing is a smaller factor in attendance costs for these students.[1]

A Number of Current State and Federal Aid Programs Already Make It Possible for Lower Income Students to Attend College Tuition-Free

- Board of Governors (BOG) fee waivers covered 45% of all Community College students in 2012-13.[2] The program allows tuition-free attendance for students meeting income eligibility or demonstrating a financial need through the FAFSA application.

In an attempt to continue meeting the community college system’s open access goals, the same law mandating the fee also included a program waiving it for financially needy students. This waiver has come to be known as the Board of Governors Fee Waiver (BOGFW). As fees have increased, the BOGFW has kept pace, making community college education tuition-free for all needy Californians for 30 years. The waiver was provided to over 5.1 million students between 1984 and 2015.[3]

- In 2016-17, Cal Grant A provides up to $12,240 for UC and $5,471 for CSU. Cal Grant B provides a living allowance of up to $1,656 at a 2- or 4-year college. Eligibility varies by family size and income, but in 2016-17, families of 4 with incomes less than $90,500 qualified for Cal Grant A.[4]

- California’s Middle Class Scholarships provided maximum awards in 2015-16 of $2,448 at UC and $1,092 at CSU. Eligibility covers families with incomes of up to $150,000 (adjusted for inflation).[5] The Governor’s January Budget, however, proposes phasing out this program.

- The UC Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan combines aid from various sources to guarantee students from families earning less than $80,000 can attend tuition free.

UC’s Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan will ensure that you will not have to pay UC’s systemwide tuition and fees out of your own pocket if you are a California resident whose total family income is less than $80,000 a year and you qualify for financial aid — and that’s just for starters.[6]

- In 2016-17, the federal Pell Grants provided up to $5,920 based on financial need.[7]

Proposals for Tuition-free College Do Nothing to Address the Primary Component of Student Debt—The State’s Increasing Housing Costs

As indicated above, existing programs already make it possible for lower-income and many middle-income students to attend college tuition-free at public schools in California. Assistance for living costs, however, is less in grant form and generally entails loans, work-study, and personal resources. As illustrated by the Community College example above from LAO and as shown in the figure below, the cost of housing and other living expenses dwarfs costs for tuition and continues to grow rapidly as the state continues to ignore the regulatory barriers that add to the cost of housing construction and that restrict the number of new units that can be built each year.

Source: LAO[8]

Rather than reform housing regulation to increase housing supply and reduce housing and rental prices, California continues to add new regulations that increase construction costs. These include existing measures for new housing such as the Net Zero Energy requirements estimated to increase the cost by $35,000 per new unit and other proposed provisions such as VMT fees and others that will expand costs further. Still, other regulations further increase the costs for homeowners seeking to bypass new home prices by doing housing improvements instead, including automatic triggering of additional costs under Title 24 energy efficiency requirements[9] and regulations for water retrofits[10] for home improvements done under a permit.

California Already Imposes a 1% Income Tax Surcharge on Incomes Above $1 Million

Proposition 63 (2004) imposed an additional personal income rate of 1% on incomes over $1 million, regardless of filing status. Funds are deposited in the Mental Health Services Fund for state and local mental health programs.

The state is not spending the full amount of this current revenue. Schedule 10 to the Governor’s January Budget Proposal projects the fund balance will be $1.7 billion at the end of the 2017-18 fiscal year or 16% more than the total projected to be raised from this tax during that period.

Reviews by the Little Hoover Commission in 2015 and an update in 2016 concluded there was little oversight or accountability on how or whether these funds are being spent:

More than a year after the Little Hoover Commission’s first look at the Mental Health Services Act, it decided to conduct a follow-up review and found that many concerns remain unheeded. . . In its January 2015 report, Promises Still to Keep: A Decade of the Mental Health Services Act, the Commission voiced concern that as money comes through the MHSA pipeline each year, the state lacks an accountability mechanism to assure taxpayers, voters, and most importantly, mental health care consumers and advocates, that the money is being spent in ways voters intended.[11]

More critically, proposals that seek to reduce college costs for a few through tuition changes—rather than costs for all by finally tackling the state’s housing cost crisis—continue to do so by proposing even more increased dependence on the state’s highly volatile personal income tax base. While funds may be available in good years, the extreme fluctuation in this income component would provide an uncertain revenue source for higher education, with cuts likely in the very years students would rely on this assistance to remain in school. Department of Finance budget data shows that revenues from the existing Mental Health Surcharge have varied by as much as $1 billion over the past 10 years.

Download Report

Sources:

[1] Legislative Analysts’ Office (LAO), Overview of Tuition-Free Community College Programs, February 3, 2016.

[2] California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, The California Community Colleges Board of Governors Fee Waiver: A Comparison of State Aid Programs, January 19, 2016.

[3] California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, The California Community Colleges Board of Governors Fee Waiver: A Comparison of State Aid Programs, January 19, 2016.

[4] California Student Aid Commission, What is a Cal Grant?

[5] Middleclassscholarships.org.

[6] University of California, Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan.

[7] US Department of Education, Federal Pell Grants.

[8] Legislative Analysts’ Office, Financial Aid Overview, March 13, 2014.

[9] San Diego Union-Tribune, New Regulation Hits California Homeowners, March 24, 2015.

[10] Sacramento Bee, Home Improvements Will Trigger New Rule on Replacing Plumbing Fixtures in 2014, December 11, 2013.

[11] Little Hoover Commission, Promises to Keep: A Second Look at the Mental Health Services Act, September 2016.