Executive Summary

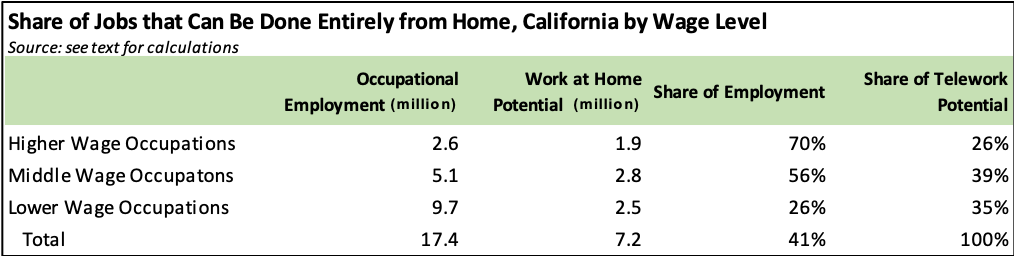

Despite being at the forefront of technological advances and innovation, California’s current policies related to teleworking have remained static. Prior to COVID-19, primarily the higher paid, highly educated Californians had the most access to the benefit of telecommuting. In an analysis of 2019 jobs data, 70 percent of all higher wage jobs (more than $100,000 average annual wage) occupations could do their work entirely from home. This, despite being able to afford to live closer to their places of work and with more income to dedicate to higher gas prices, other expenses related to super-commuting, and the resources to secure quality child and other dependent care.

COVID-19 and corresponding stay-at-home orders forced employers and employees to quickly adapt to telecommuting as the standard mode of working. According to recent federal data, likely more than 40 percent of workers across the nation are maintaining their household incomes through telecommuting. The rapid shift to telecommuting has disproportionately benefitted higher-wage and salaried employees, whose jobs can be done remotely under the state’s existing labor and employment laws. This smooth transition can be seen in the state’s income tax withholding data, which is relatively unchanged since the same time last year. Because of the steeply progressive nature of the state’s income tax, this outcome confirms that higher wage Californians have been able to retain their jobs and household incomes more fully in the current crisis, and they have done so largely through telecommuting.

The current pandemic has created a substantial shift in attitudes toward telework. Not only have employers made significant investments in technologies and protocols to support telecommuting, but employees realize that they can be just as and in most cases more productive working from home. As is discussed later in this report, as many as 40 percent of California workers could do their jobs entirely from home once the COVID-19 pandemic is over. More could so on a less regular schedule, and more could telecommute in future years as technology and the nature of work continue to evolve.

However, absent actions from the state, telecommuting will continue to be a luxury that benefits primarily the higher-wage workers in the state. In fact, only 26 percent of teleworkable jobs in California are in these higher-wage occupations. Another 35 percent are in lower wage jobs (up to $50,000 average wage) that could telecommute, but have not by and large because of restrictions in state law. In order to create equal access to telecommuting now and into the future, the state must modernize its workplace rules in order to give employers and employees flexibility they both want and in the current crisis circumstances need.

A flexible work environment is even more critical now, as working parents work to balance educating their children while ensuring a stable and secure income from their job. Salaried employees, who are not restricted by meal and rest break requirements, restrictions on work days, and other provisions of the state rules, are better able to create the work/life balance required to be both a full-time employee and full-time educator for their child/children. Lower-wage hourly employees with inflexible work schedules, as mandated by law, will likely be forced to choose between educating their children and receiving full pay (if they can remain employed at all). State workers across all wage levels have access to this work flexibility now; lower wage workers in the private sector should as well.

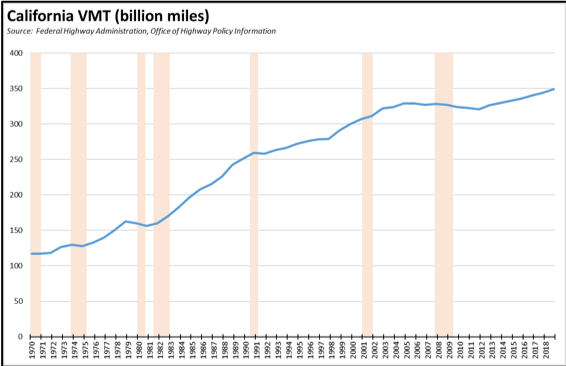

Beyond the short-term need to address equal access to telecommuting options, the state should promote long-term telecommuting as part of its climate change agenda. Telecommuting can help the state achieve its greenhouse gas and air quality emission goals across all workers. Over the past 5 decades, the state has adopted numerous policies and regulations in an attempt to reduce how much Californians use single occupant vehicles. None have been effective and consequently have only raised the costs of housing and commuting, costs that so far have disproportionately affected lower-income Californians. Telecommuting is the only option proven to reduce miles traveled and its associated emissions, and it does so without costs but instead savings that increase effective incomes for those able to use it.

While the transition to telecommuting has been developing naturally for the past two decades, COVID-19 has accelerated the transition and demonstrated its co-equal benefits for worker incomes and the environment. The only barrier to fully realizing the benefits for Californians of all income levels continues to be state law, policies and regulations.

Even Before the Current Crisis, Workers were Choosing to Telecommute. As a primary commute mode, working at home (telecommuting) grew 602% since 1980, doubling since 2000 alone. Telecommuting first passed public transit use in 2010, and has remained consistently above since 2014. Even before the current crisis, telecommuting was on track to bypass carpooling by 2029, and in the present circumstances clearly already has done so. In 2019, 6.3% of workers in California worked at home as their primary commute mode (vs. 5.7% for the US). Only 5.2% relied on public transit.

And Even More Workers Chose to Telecommute Part of the Time. Federal data shows 19.5% of workers (28.1 million) nationally worked at home for pay at some point in the year, and 14.7% (21.3 million) worked exclusively from home ranging on schedules from less than once a month to 5 or more days a week. Those working exclusively from home did most frequently 1-2 days a week, but 8.1% of all workers worked from home at some frequency within a regular weekly schedule.

In the Current Crisis, Likely Over 40% of Workers are Maintaining Household Income through Telecommuting. Recently released federal data indicates that in June, 31% of US workers worked from home as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Adding in those who telecommuted prior to the crisis, over 40% of the workforce is now maintaining their jobs and household incomes through this arrangement.

Federal Workers Already Telecommute. Federal telecommuting policies stem from a 1994 directive from President Clinton ordering this option primarily to expand flexible family-friendly work arrangements. The policy was then expanded greatly under President Obama and became law in 2010. While the Trump Administration subsequently began rolling this policy back, 22% of the federal workforce teleworked at least some portion of their regular work week in 2018.

State Workers Will Telecommute More. In spite of its notable absence in the state air and climate change plans, telecommuting became formal state policy through legislation in 1990. In the recent Budget May Revise, Governor Newsom highlighted his intention to expand substantially teleworking by state employees as a means to reduce the amount workers drive, improve worker productivity and jobs satisfaction, reduce turnover, improve the delivery of state services, and reduce office space and energy use and thereby reduce the state’s carbon footprint.

Post-COVID, 40% of All Workers in California Could Do Their Jobs Entirely at Home. In the post-COVID economy, the issue will not so much be which jobs can be done from home as it was asked in the past. The question instead will be which workers will want to go back to an office.

California innovation made the current rapid shift to telecommuting possible, providing an economic lifeline here and in countries around the globe. Many jobs previously considered less amenable to this option are now being done at home. The transition was quick, and was greatly facilitated by changes in technology over the past two decades. In post-COVID California, much of this shift can be maintained; an estimated 40% of all wage and salary workers could do their jobs entirely from home. Weighted by wage, about 50% of all wage income could be earned entirely at home—a prime factor in the fact that California income tax withholding since March has been running at 2.4% above the 2019 numbers even during the current crisis.

The Potential Upside is Even Higher. Continuing changes in technology and applications will make other occupations teleworkable as it expands into a standard work arrangement. The 40% estimate covers only wage and salary workers; the self-employed will be able to expand telecommuting as well as it becomes more of a working norm.

The 40% estimate covers only occupations that can be done entirely at home; many others have at least a portion that can be done from home. Meetings, conferences, and contact with customers in the current crisis is now being replaced by phone and video conferencing, and can continue to reduce work related travel as telecommuting expands. The number of super commuters—those with one-way commutes of greater than 50 miles—grew from 10.7% of workers in 2002 to 15.2% in 2017. They will be more likely to telecommute, increasing the potential emissions benefits from a shift to telecommuting.

Higher Wage Occupations Are More Likely to Telework. In the past, workers with a higher educational attainment and a higher wage, knowledge-based occupation were more likely to telework. The same results are in the analysis of the 2019 job and wage data—70% of all higher wage (over $100,000 average annual wage) occupations could do their work entirely from home.

But Three-Fourths of the Potential would Come from Lower- and Middle-Wage Workers. Higher wage occupations are more amenable to telework, but there are fewer workers in these occupations overall. From the analysis of the 2019 data, higher wage workers represent only 26% of the total workers who could telecommute. Middle wage occupations ($50,000 to $100,000) comprise 39%, and lower wage occupations ($0 to $50,000) 35%. The economic and environmental potential in fact depends on employers being able to offer telecommuting to this lower wage group.

Achieving the Full Benefits from Telecommuting Depends on Giving Access to All Eligible Workers. There are few regulatory barriers to expanding telecommuting to the middle and high wage occupations. Some may become better addressed systematically as telecommuting expands, but these issues can and have been handled through employer policies. The lower wage occupations, however, in essence cover the non-exempt employees under the state’s wage and hour laws, that limit the flexibility required to extend telecommuting fully to these workers. The risk to employers is amplified under the Private Attorney General Act (PAGA), which opens up employers to substantial penalties for even minor or paperwork infractions. In most cases, changes to these laws themselves are not required. Instead, recognizing that in essence teleworkers become their own front-line supervisor for compliance with these rules, additional flexibility could be achieved by: (1) modifying the currently cumbersome notice and voting requirements to adopt flexible schedules for workers who choose to telecommute or (2) allowing employers/employees to adopt flexibility provisions that are already being used for state employees. These issues are particularly important due to the fact that as the minimum wage rises, so will the share of workers subject to these issues.

Telecommuting at This Level Furthers the State’s Climate Change & Air Quality Goals. As the foundation for the state’s climate change program, AB 32 gives the designated agencies broad authority to develop regulations to achieve “. . . the maximum technologically feasible and cost-effective GHG emissions reductions . . .” Efforts to date to reduce the amount Californians drive their cars and trucks contain only costs. After nearly 5 decades of repeated trying, there has been little or no effect on emissions, and in fact emissions from this source continue to grow. With a renewed reliance on land use strategies associated with SB 375 and SB 743 that cannot work given California’s jobs and development patterns and policies, the current program ensures that only more costs will be imposed especially on lower wage workers who are least able to afford them.

Telecommuting at the levels above instead have the (scoping level) potential to reduce the amount Californians drive by up to 60.7 billion miles a year (17% of VMT) based on the 2019 numbers, and up to 66.5 billion miles by 2030. The associated GHG reductions range up to 24.1 MMTCO2e (10% of the cumulative gap remaining to reach the state’s 2030 goal) from the 2019 numbers, and up to 26.3 MMTCO2e by 2030. The potential emission benefits are even larger taking into account the upside factors listed above. And these benefits can be achieved at no cost to the public agencies or the public, but instead with substantial cost savings to workers who choose to telecommute.

Telecommuting at This Level Furthers Other Goals as Well. Additional household and state policies goals that can be furthered through sustained, expanded telework include: (1) Allows greater work/personal balance by returning an hour or more a day previously used for commutes and allows balancing of family demands that are especially critical as schools remain closed. (2) Expands dependent care options that instead have become limited as day care slots have shut down in the current crisis, and are likely to remain costly and in short supply as the recovery unfolds. (3) Fosters worker satisfaction by giving them more flexibility over their work process and schedules, resulting in higher productivity, creativity, lower job turnover, and overall job satisfaction. (4) Combats growing income inequality by allowing workers to realize higher effective incomes through immediate savings on commute costs, reducing or foregoing other costs for dependent care and other household needs, and expanding the options to find housing they can afford without having to resort to overcrowding. (5) Opens new economic development paths for lower income communities through a potential network of telecommute centers in these communities throughout the state, using them to accelerate introduction of telecommute jobs until workers can afford to work out of their own homes, linking with Community Colleges for training in teleworkable occupations, and refocusing employer recruiting outside the coastal urban centers that accounted for the bulk of better-paying jobs growth over the prior decade. (6) Expands economic resiliency through a model that has maintained jobs and incomes for a large portion of the workforce even under the current crisis conditions. (7) Expands public health resiliency through a model that has reduced the spread of COVID-19 and the only strategy that has been deployed with economic benefits rather than substantial costs. (8) Expands fiscal resiliency through a model that has allowed state and local governments to retain a revenue base essential to the current crisis response and other essential public services. (9) Expands a model that will take other provisions in the climate change Scoping Plan that now exist as only modeling benefits and assist them in achieving the emissions reduction potential.